It appears that by the end of 1917, the local recruiting committee for the Shire of Alberton had ceased to operate. As had happened after the failure of the first referendum, the members of the recruiting committee no doubt considered that their efforts, in the face of what they saw as national apathy and opposition, were neither valued nor effective. From the start of 1918, Shire of Alberton council papers indicate that all correspondence from the State Recruiting Committee was being tabled at council meetings, suggesting that the Council itself had taken over responsibility for recruiting. Also, there is no correspondence in the relevant Shire of Alberton archives that deal with the local (Yarram) recruiting committee past early September 1917. On that occasion, there was a letter from the regional recruiting officer, based in Sale, seeking funds to cover the fitting out of a waggon – … of a nature similar to a drovers waggon – that he could use to travel to the more remote ‘back blocks’ so that he could … gain access to eligibles remote from the railway. He was seeking funds from all 23 local recruiting committees in Gippsland. The proposal was that after the trip the waggon would be sold and the money raised would be returned to the committees. The officer – Lt Radclyffe – received the following, rather terse, reply from G Black, Secretary of the Yarram Recruiting Committee. It was dated 6/9/17.

In reply to your letter of the 3rd inst., soliciting a contribution towards a turn out to travel the back blocks, I have to inform you that this Committee has no funds.

From the end of 1917, the only time that the local recruiting committee reprised its role, albeit in a limited way, was in May 1918. This was when the (Victorian) State Recruiting Committee launched a recruiting drive focused on country Victoria. The scheme was referred to as the Itinerary Training Scheme and, over a period of two months, 3 recruiting teams covered the entire state. Each team consisted of approximately 35 AIF soldiers, with an army band of 16 members and a ‘platoon’ of another 15 soldiers – made up of both returned men and those about to embark – as well as a small headquarters staff. Each team also had a Victorian federal politician – J H Lister MHR, J W Leckie MHR and G A Maxwell MHR.

The 3 teams travelled from country town to country town – normally via train – and over a period of between 2 and 4 days, depending on the size of the town, conducted a recruiting drive. There was a standard program for each visit which included some form of civic reception for the AIF members, at least one major concert, several recruiting appeals, a major march/procession though the town and a (Protestant) memorial service as well as a requiem mass organised by the local Catholic priest.

The Itinerary Training Scheme – sometimes referred to as the Itinerary Recruiting Scheme – was specifically targeted at ‘eligibles’ and, in theory, the intention was to identify all the local eligibles and make a personal appeal to each of them. But this was difficult, particularly where the eligibles resided in outlying areas and also, of course, when the eligibles did not want to be contacted. The following extract from the 27/6/18 edition of the Swan Hill Guardian and Lake Boga Advocate highlights some of the challenges. As indicated, J W Leckie was one of the 3 members of federal parliament attached to the recruiting teams.

Mr. J. W. Leckie, M.H.R., who is touring the country with one of the parties under the itinerary training scheme, tells some amusing stories of the experiences of the party.

At a small country town out of Ballarat, members of the party were “beating” the outlying parts for eligibles, when a baker’s cart was seen standing outside a house about 100 yards away. As the party approached, an athletic looking young driver came out of the house, and was about to mount the step, when he saw the “khaki” in the distance, and instantly disappeared. The party was mystified at his quick disappearance, but when the door of the cart was opened he was found crouched among the loaves.

In another instance a couple of soldiers visited a farm house to interview an eligible whose name had been submitted by the recruiting committee. As the soldiers approached the farm house they saw a young fellow bolt into the stables. They searched for him, and eventually he was discovered hiding under a bundle of bran bags in the loft.

Two eligibles were reported in another town to be working in a garage, and the recruiting sergeants paid the garage an unannounced visit. The eligibles, however, got the “tip,” and the sergeants saw them scale a high fence and escape into an adjoining property. They did not return to work until the party left the district.

There were claims in the media at the time that the Itinerary Training Scheme was very successful and up to 500 men were recruited. However, the numerous accounts in country newspapers suggest otherwise. They indicate that while the visit of the AIF party prompted feelings of patriotism in the local community – and certainly the soldiers were well received – the actual number of eligibles who could be persuaded to enlist was very small. As will become obvious, this was certainly the case in relation to Yarram.

The Itinerary Training Scheme came to the Shire of Alberton in mid May 1918. And at this point, the local council appears to have requested that a separate committee be formed to manage the arrangements. This was when the previous recruiting committee was reformed. B P Johnson called a public meeting at the start of May and a committee was set up – it gave itself the title Itinerary Recruiting Committee – with the sole purpose of organising the visit. The key people involved in the committee were B P Johnson, E T Benson, J W Fleming, H C Evans and W F Lakin and, with the single exception of Herbert C Evans, all of these had been involved in the previous local recruiting committees.

The Gippsland Standard and Alberton Shire Representative outlined the agreed program in its edition of 1/5/18. The AIF team was to arrive at Alberton Railway Station on Monday 13/5/18 at 3.00 PM. Jonson’s committee had to organise a fleet of private cars to transport the men to Yarram. The men were to be dropped on the outskirts of town where they were to form up and then march, with the band leading, down Commercial Street to the Shire Hall for a civic reception. The committee had to make sure that the town was decorated with flags and bunting. Businesses were to be closed and the townsfolk were expected to join in. After the civic reception the men were to be taken to their billets – the organisation of billets for all the men was another responsibility of the committee – and then later that evening they were to stage another town parade which immediately preceded the major concert to be put on by them. In the morning of the next day -Tuesday 14/5/18 – there was to be another town march and a special Appeals Parade. The afternoon was set aside for what was termed ‘Personal appeals to eligibles’. Again, the committee was to organise transport for this so that the AIF recruiters could go to the outlying townships. Presumably, the committee – or perhaps the council – also provided names and addresses. That evening there was to be another parade and recruiting rally back in Yarram. On the Wednesday, 15/5/18, the Catholic community was to organise a requiem mass in the morning, and this was to be followed by another parade and appeals. In the afternoon, yet another parade was to herald the 3.00 PM Memorial Service which was to be held at the Showgrounds or, if the weather was bad, in the Shire Hall. That evening there was to be another parade and then the final recruiting rally. On the Thursday – 16/5/18 – the team was to leave from Alberton for Leongatha at 11.45 AM, after they had been transported by private cars from Yarram, and after the final parade set down for 10.30 AM. Obviously, the whole affair required a significant degree of planning and preparation. The so-called Itinerary Recruiting Committee was set up as a short-term working group and it disbanded after the visit of the AIF.

The local paper featured extensive reporting of the events associated with the recruiting drive in Yarram from 13 to 16 May, 1918. The reports appeared in the editions of 15/5/18 and 17/5/18.

The AIF contingent arrived as planned and, having been transported by private cars from Alberton, the men formed up and marched into town, with the AIF band leading. The town’s main street had been extensively decorated with flags and the troop was followed by a large number of townspeople. The men were under the command of a Lieutenant Smith.

The civic reception incorporated afternoon tea and the men were welcomed by the Shire President – Cr T J McGalliard – who hoped that their efforts at recruiting would be successful. McGalliard highlighted what he saw as the dire situation on the Western Front and claimed that the British army was … now far too small an army to stand up against the mighty German hordes. He urged that the struggle had to be maintained until the American troops could make the critical difference. Referring directly to recruiting, he commented proudly on the extent to which the locals had done their duty and enlisted. But he also declared that … every man who was fit and eligible … needed to enlist.

Cr Barlow then expressed gratitude for the size of the crowd at the event and expressed pride in the AIF members who had joined them. He noted that some of them … were going to the front … and he declared that everyone owed ‘a debt of gratitude’ to the returned men also there. Another councillor, Cr O’Connor, expressed anger at the current political situation – he appeared to blame Hughes for not moving quickly enough on second conscription referendum – and frustration over those who refused to enlist:

There were plenty who had good reason for not enlisting, but there were hundreds of thousands of shirkers still in the country, and would be there after the other men had done their duty. They could not be induced to join the colours. They were going to let the other fellow do their work.

B P Johnson also spoke and gave the example of Port Albert where, he claimed, there was not one ‘eligible’ left. He declared that the rest of the district had to copy the example of Port Albert. The claim that every eligible in Port Albert had already enlisted was common at the time.

The officer in command, Lt Smith, thanked everyone for their hospitality. He declared that he was more optimistic than the speakers who had preceded him and was sure that the people of Gippsland would support recruiting. He noted that Gippsland was ‘God’s own country’. He also explained how he had a competition going with the equivalent team then in Echuca. He reassured them that Gippsland was just in front and he declared that he would be able to rely on the local people and … was sure that the citizens of Yarram would be second to none.

That night what was billed as a ‘patriotic concert’ was held in Thompson’s Hall. The local paper described how when the stage curtains were drawn back there was a ‘big display of flags of the Allies’ and seated on the stage were the uniformed men. The AIF Band then struck up the National Anthem.

There was a strong negative tone to all the speeches that night. The way the paper described it, the speakers appeared to vent their frustration over the failure of the 2 conscription referenda and therefore the need to appeal for voluntary enlistments. For Imperial Loyalists, the situation was one of national shame and typical of this sentiment were the opening remarks from the Shire President (McGalliard). He claimed to have received recently 3 letters from relatives who were serving overseas. From one letter he quoted the writer’s belief that … Australia was divided into one lot white, and one lot a dirty, motley yellow. From the second letter he quoted the claim that … Australians did not think as much of their soldiers as the Canadians did, and what was more – it was true. The third letter was from a doctor … who was so disgusted at Australia fighting over petty things instead of considering the sacrifice being made by the boys at the front that he stated “that if it was not for you, mother, I would not come back to Australia again.”

According to the local paper, the most common argument presented that night was the claim that those who had enlisted had been promised, at the time they enlisted, they would be reinforced, yet now that promise was being broken. The chair, in his opening remarks, … emphasised the great need of sending reinforcements to relieve those over there, or they would either have to die or be maimed. The local MP – J McLachlan MLA – one of the invited speakers, declared:

The men who went away had gone with an assured promise, but had not been reinforced to the extent that they ought to be.

Sergeant Perry, a returned soldier and one of the key AIF recruiters there that night, referred back to the very start of the War and declared that:

The one and only thing they [the initial volunteers] were told was that they would be supported. That was the obligation and responsibility placed on those who remained. Not one of them raised any objection to the Government and the pledge that those men would be supported to the last man and and last shilling.

Sergeant Perry went on to labour the point that the lack of reinforcements was having dire effects on the men at the front. He noted that … Those Australians who were fighting in France were becoming physical wrecks for the want of a spell. Some of them had been in the battle since since 1914. He then proceeded to give personal examples of the effects that the lack of reinforcements had. He said he knew of … one boy who was wounded ten times, and on the last occasion had to have an arm and leg amputated. He then made the point that this lad … should have been back 18 months ago. Perry gave statistics on the extent to which casualties had more than decimated battalions. He claimed that of the 1,000 men of 2 Battalion – the unit he left Australia with in October 1914 – only 5 originals remained.

Other themes touched on that night included the bravery and very recent success of the AIF in Europe which had … averted a calamity by driving back the Huns. There was also the usual contempt for those ‘cowards’ who refused to enlist as … the meanest things God ever gave breath. Building on the fear of the ‘enemy within’ and the direct threat posed by Germany – given more credibility at that point by the talk of German raiders off the coast and the claimed activities of local agents and spies – speakers referred to Hughes’ comments about the War being … on our shores, showing that the Germans were at work here. There was also the claim that Australia was an obvious target for Germany acquisition:

This country was most suitable for the enemy with all its great resources, and with a limited population of 5,000,000 the enemy desired this country.

Speakers also criticised those who wanted a ‘negotiated peace’:

Some people were crying out for peace by negotiation, but no man in Yarram could raise his head if they had such a peace. What they wanted was a peace by victory by drawing from all sources of the Empire that man power which they think is available.

On the night, people would have been confused over the question of how many eligibles still remained in the district. The conventional wisdom was that there were very few ‘eligible’ men left in the district. As noted, B P Johnson, for example, was fond of citing Port Albert as an example of a town in the district where there was not one single eligible left. There was also the high number of recorded enlistments from the area. The previous series of posts covering enlistments associated with the Shire of Alberton puts the number of enlistments to the end of 1917 as close to 750. Also, figures from the State Recruiting Committee of Victoria at the end of 1917 revealed that, between January and December 1917, Gippsland had been the country electorate with the highest number of enlistments. The common belief was that country Victoria had done very well with recruiting, Gippsland had been the most successful of all the country regions and that, by contrast, metropolitan Melbourne was the place where all the eligibles resided. This was the gist of comments made at the concert that night by J McLachlan MLA:

In Melbourne there were 20,000 eligible men, who were called upon daily to take the places of their brothers, and there were many eligibles in Gippsland; although Gippsland had done remarkably well.

However this conventional wisdom was turned on its head by comments made by Sergeant Perry who claimed he … knew from official figures that in the subdivision of Yarram there were 839 eligible men and fit to go. On top of that, they had failed to send 65 recruits a year. They had failed badly.

On Perry’s figures, the Shire of Alberton generally, and Yarram specifically, had major concentrations of men who refused to enlist. In fact, on his figures there were more eligibles still in the area than men who had enlisted. Perry’s figures came from a Commonwealth report prepared for the Department of Defence in April 1918. It claimed to show – by subdivision of federal electorates – the ‘Estimated Number of Males between 19 and 44 years at present in Australia’ . It was used, as part of the Itinerary Training Scheme, to highlight just how many eligibles remained. It came with the appeal that … it behoves every individual in the Commonwealth to do his or her best to induce the eligible men to offer their services as early as possible… [letter from State Recruiting Committee of Victoria, 22/4/18]. But the figures were only estimates and, given all the variables involved, vague estimates at that.

Overall, there was certainly no evidence that there were 839 eligibles just in the Yarram subdivision. When the Exemption Court had been held in Yarram in October 1916 – see Post 93 – there were 124 applications for exemption and, based on this figure, it seems reasonable to argue that the number of eligible men who had not enlisted was in the general order of one hundred. Nor is there any evidence that there was an isolated, outlying settlement where there was a concentration of eligibles. Moreover, as has been noted previously, many of these so-called ‘eligibles’ failed medicals when they did try to enlist. The preoccupation with identifying and shaming eligibles meant that under-age and already ‘rejected’ young men were often unfairly targeted. The other complication with country towns was the number of itinerant workers who moved though the district.

In fact, events at the concert that night helped demonstrate the lack of eligibles in the district. At the end of the patriotic concert, after all the exhortations, the call went out and 16 ‘men’ stepped forward. Dr Rutter examined the men afterwards and, immediately, 7 failed the medical. Of the others, some were rejected because they were underage and others must have failed subsequent medicals. In the end, only 4 of the 16 were accepted as genuine recruits; and of the 4 it appears that only 2 – George Clarke from Wonwron and Silvester Callister form Devon North – actually enlisted. Admittedly, eligible men who had no intention of enlisting were not going to attend such a ‘patriotic concert’ and draw attention to themselves but, for all the qualifications, by that point in the War there was not a large pool of eligibles in the Shire of Alberton. At the same time, in the heightened paranoia and patriotism of the time, the quest for eligibles was relentless.

Outside the men who answered the call at the patriotic concert, there were only an additional two or three local men who volunteered in this period of mid May 1918. Even if this additional handful of enlistments was influenced by the presence of the AIF recruiting party in Yarram, it is clear that the overall success of the visit was very limited.

Those attending the concert that night were treated to a full program of popular entertainment. The formula of items had been tried and tested all over country Victoria and the show was designed both to attract the locals and make the soldiers on stage the focus. Newspaper accounts from other towns stressed how much the locals enjoyed having the soldiers in their town and how entertaining the concerts and parades proved. The type of entertainment that featured in Yarram that night was recorded, in detail, by the local paper. For example, after the opening remarks by the Shire President, the paper reported:

The A.I.F. Band then contributed a selection, followed by a chorus “One Man went to Row” by the members of the A.I.F, which was received with loud encores, and they sent out another volley, “Has Anybody here seen Kelly.” The local humorist, Mr. C. E. King-Church, amused the audience with “I had a row with my Wife last night.” The chairman then introduced Private S. Cooke, the hand-cuff king, who gave some clever exhibitions, releasing himself from a straight-jacket, and ropes, chains and hand-cuffs, after being securely (?) fastened by a body of gentlemen from the hall. His feats brought forth rounds of applause. Another selection was rendered by the A.I.F Band.

And interspersed between the calls for recruits, dire warnings about the state of the fighting in France, praise for the men of the AIF and the haranguing of eligibles, there was an ongoing series of popular items. Some of the items would have appeared very exciting, particularly for any children in the audience. There was certainly a martial theme to it all:

Mr. Evans sang “John Bull” in his capable style, and meeting with loud encores favoured the audience with “When the Boys Come Back.” An exhibition of bayonet charging was given by several members of the A.I.F. Mr. King-Church again humorously treated his hearers by singing “Picking Poppies.” Another band selection was rendered by the Military Band.

The other key event that was written up in the local paper (17/5/18) was the memorial service held the day after the concert. It was held – indoors because of the rain – in the afternoon after the Catholic requiem mass had been held in the morning. Returned men were seated on the stage with the clergy. The visiting AIF band provided the music.

The 3 Protestant ministers involved were Rev A R Raymond (Anglican), Rev S Williams (Presbyterian) and Rev C J Walklate (Methodist). Rev Raymond’s son had been killed in action (9/4/17) and Rev Walklate’s brother had also been killed (22/10/17). Rev Williams drew attention to these deaths when in his opening remarks he noted he was … fully conscious that they had on the platform ministers whose family circle had been broken as a result of the war.

During the service, the names of 49 local men who had been killed were read out by Rev Walklate.

The first prayer was for ‘King and Country’ and the focus in the address delivered by Rev Williams was the Empire. As noted previously, many times, Protestantism was the religion of the Empire. Williams tied the deaths of the local men to unquestioning support for Britain and the Empire:

When he read that list of the dead they remembered they were men who stood as soldiers irrespective of creed or denomination to maintain and reserve for Britain the glory of her exalted position, a position that had come by her noble work.

He reminded the audience how they had to … remember their boys as they remember great men and their sons as men who stood to make Britain what she is. These men have handed their life over for the whole world. They were men who had, unflinchingly, answered the call from the ‘mother country’:

When the shadow began to fall on the British Empire, as it crept away and reached to Australia, and the call came from the old mother, the boys in their hearts turned to their parents and said they were going to the war.

Williams set the proud reputation of the Australian soldier within its Imperial context:

Another characteristic in the Australian soldier was that he could take his place alongside the armies of the world. They possessed courage that made them not afraid to take their part. Courage of the kind that General Gordon possessed when he was in the midst of the savage races of Africa. Their courage was shown on Gallipoli, and in France where the men went forth to raid the camps of the enemy at night. In the words of Nelson, who said “We are brothers, we are men, and we conquer to save.” That was the spirit. They were not fighting for the extermination of any race, but liberty, peace and righteousness in all its quarters, to bring about the universal brotherhood of the world.

The focus on Empire was an absolute given in any recruiting campaign. As an example, in early January 1918, when the State Recruiting Committee of Victoria wrote to all the local recruiting committees – at a time when it was trying to re-establish confidence in the voluntary system after the defeat of the second referendum – it made a classic declaration of commitment to the Empire:

It would be superfluous to expatiate on our duty to the Empire because in addition to our being an integral part of the Empire, no sacrifice made by us would be adequate to compensate the Motherland for the assistance and protection she has always unconditionally given.

As indicated, the memorial service – and requiem mass – were intended as set pieces in the overall theatre of the Itinerary Training Scheme and Lieutenant Smith, from the visiting AIF party, gave a short appeal for recruits:

He asked all in this time of grave crisis, when the fate of the Empire hung in the balance to realise their duty.

The AIF band played the popular and moving ‘Dead March’ and the service concluded with the National Anthem.

The Itinerary Training Scheme over April – May 1918 was, in theory at least, designed to boost recruiting by sending out 3 specialist AIF teams to cover all of country Victoria and track down all eligibles. Again, in theory, when these eligibles were confronted with the realities of the present state of the War and their innate sense of patriotic duty was revealed to them, by way of a personal interview with the AIF recruiters, they would enlist.

The actual experiences in the Shire of Alberton in mid May 1918 suggests that the scheme failed. Certainly, estimates of the number of eligibles were overblown, at least in part because many who were seen as eligible had no chance of meeting the medical standard or they were underage and their parents refused to give permission. Moreover, the previous 4 years of recruiting had shown that locals in the Shire of Alberton had enlisted in great numbers and it was definitely not the case that there remained a vast, untapped pool of eligible recruits. Doubtless, there were some genuine eligibles in the local area but, on the face of it, the visit of the contingent from the Itinerary Training Scheme appeared to be out of all proportion to the potential number of recruits. At the same time, the visit by the AIF was a wonderful opportunity for the locals to demonstrate their support for the War effort, their belief in the greatness, newly won, of the AIF itself, their sense of the debt they owed to the soldiers and, of course, their loyalty to the Empire. Moreover in a local community that had – twice – strongly supported the Government’s push for conscription and constantly proclaimed its total support for the War effort, many would have seen the problem with recruiting as not of their making. They were more than happy to participate in the likes of patriotic concerts and support all recruiting appeals, but they hardly felt guilty for the overall situation.

One week after the AIF visit to Yarram, the following letter appeared in the local paper. It was signed by B P Johnson, Chairman and E T Benson, Hon Secretary of the Itinerary Recruiting Campaign Committee:

Sir, – It has been brought under the notice of the committee that a certain gentleman in the town has been accused of supplying names of eligibles to the recruiting officers. This is altogether untrue and in order to remove any misconception, we are directed by the committee to inform the public through your column, that the gentleman gave no information of that kind at all.

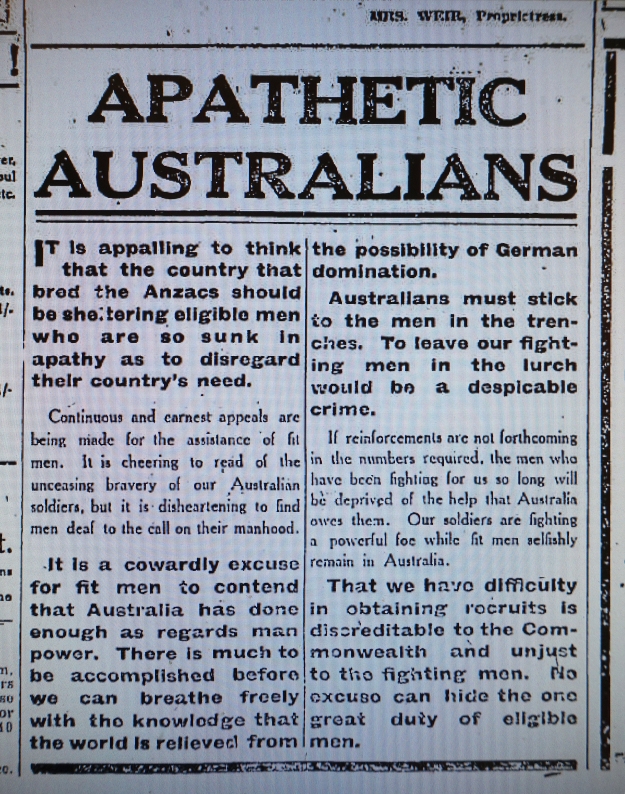

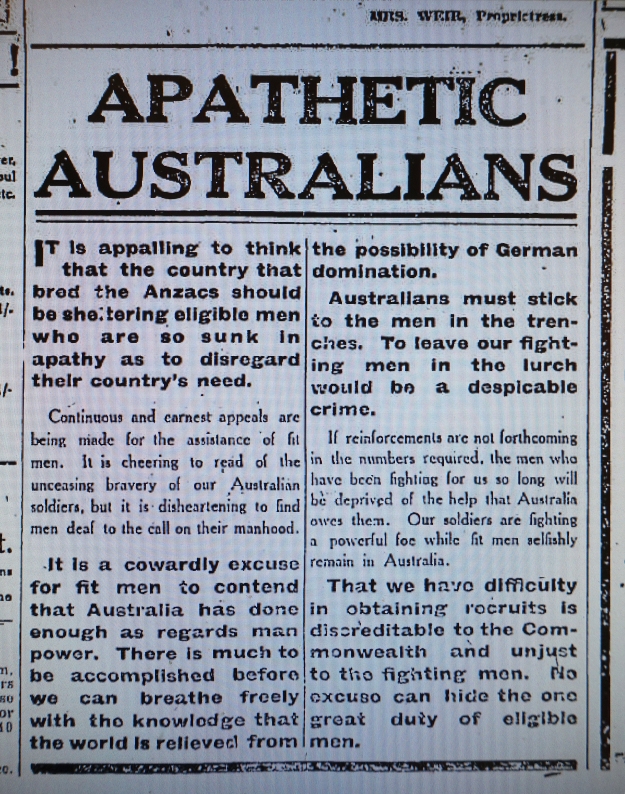

There was no further correspondence on the matter and no other related report in the local paper. The claim in the letter is hard to understand. As noted, the very purpose of the whole Itinerary Training Scheme was to identify and then confront all the eligibles in a district. Local recruiting committees were meant to provide names and it was the role of committees such as the one chaired by Johnson to provide the transport so that teams of recruiters could visit the eligibles, even if they resided outside the town limits. Even if the local (Yarram) recruiting committee was no longer actively functioning, its previous work – to the end of 1917 – would have meant that the names of local eligibles were known. Moreover, notices like the one below appeared in virtually every edition of the local paper. Everyone’s attention was focused on the local eligibles. Therefore it seems odd that there were these claims and counter claims over the actions of a single – unnamed – individual in revealing the names of eligibles. Perhaps Johnson and Couston were concerned that just one individual had been singled out as the guilty party. However, overall, the letter merely confuses the larger reality that extraordinary pressure was being applied to force the enlistment of those young men identified as eligibles.

Gippsland Standard and Alberton Shire Representative, 28/6/18 p4.

References

Gippsland Standard and Alberton Shire Representative

Shire of Alberton Archives (viewed Yarram, May 2013)

File: Correspondence etc of Recruiting Committee. Formed, April 26th 1917 (Box 379)

State Recruiting Committee of Victoria

Circular Memo No. 226, 10/1/18

Circular Memo No. 287, 22/4/18